|

About Russian warlords and their Assyrian connection August 1921 somewhere on the Russian-Mongolian border. A lonely warrior on horseback wanders through the endless steppe. He has lost most of his uniform and Mongolian talismans are swaying on his naked chest. It is the last ride of Ungern-Sternberg, the Mad Baron. His Mongolian soldiers will soon seize him and hand him over to the Red cavalry in pursuit of the small army that Ungern has lead from Mongolia into Soviet territory. And so the legend grows – the exploits of Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, the most notorious partner in crime of the Cossack warlord Grigori Semenov in the Siberian Far East during the Russian Civil War.

Assyrians and Cossacks

In the autumn of 1914 Great-Britain, France and Russia have declared war on Turkey. In the spring of 1915 the Turkish government orders the mass deportation of the Armenians on its territory. The whole Armenian population is driven out of its homeland in eastern Anatolia and an awful number of Armenians is exterminated by Turkish zaptieh and Kurdish bands, while the survivors of these forced marches are left to their fate, without food or shelter in the Syrian desert.

Mar Shimun's homeland - Hakkari Mountains

The Russians send a small expeditionary force of 400 Cossacks to the Hakkari Mountains. The Cossacks advance towards Oramar, the stronghold of the Kurdish chieftain Soto. Agha Soto is a fierce enemy of the Assyrian mountaineers. He sacks their villages, steals their flocks, he abducts their women and murders the male villagers. The Russian Cossacks are unaware of this. Blinded by Soto’s oriental hospitality, they accept his guides to lead them through the mountain passes. In a deep gorge the Cossacks are ambushed. Soto’s clansmen and other Kurds attack them from all sides and they are slaughtered to the last man. The 18 Cossacks who have stayed behind in Soto’s home as his honoured guests are massacred as well. So much for this Russian attempt to relieve the Assyrians of Hakkari in the summer of 1915.

The Assyrian mountaineers can only rely on themselves. They break through the enemy lines, they suffer heavy losses when they flee from Hakkari, but the greater part of them survives and most of them become refugees in the Russian occupied northwestern part of Persia. In this region west of Lake Urmia they are among other Christians, Assyrians of the plain, who have been living there for many centuries.

Massacre at Gulpashan

Lake Urmia in northwestern Persia

Gulpashan is one of the most important and prosperous Assyrian villages in the Urmia plain. Paul Shimmon, an Assyrian who has returned to his homeland after his studies in the USA, describes what has happened in Gulpashan. The sister village of Gogtapa has already been plundered and burnt by Muslim mobs, while Gulpashan is at first left in peace. Shimmon mentions that this is probably due to the fact that one of the Assyrian village masters is related to the German consular agent in Urmia. The latter has sent his servant to Gulpashan and Turkish soldiers guard the place.

Gogtapa - Assyrian graveyard

In January 1916 Patriarch Mar Shimun, acting as the leader of the united Assyrians, visits the headquarters of the Russian Caucasian Army in Tiflis (Tbilisi), the capital of Georgia. He is received there with great honour by Grand Duke Nicholas, the Tsar’s uncle and the commander in chief of the Russian Caucasian Army. The result of the meeting is that the Russians agree to supply the Assyrians with weapons and ammunition. After Mar Shimun’s return the Russian consul Nikitin, stationed in Urmia, publicly reads the telegram in which Tsar Nicholas II expresses his gratitude towards the Assyrian Patriarch ‘for the help he has rendered in the war and for his willingness to co-operate with us.’

Soldiers are recruited among Mar Shimun’s mountaineers, they are trained by Russian officers and in the autumn of 1916 two Assyrian battalions are ready for battle. Russian protection however won’t last much longer. The Tsarist Empire is about to collapse in the turmoil of the revolution of 1917.

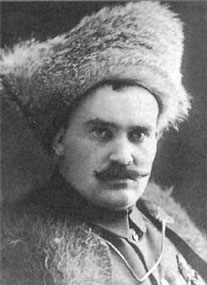

Enter Semenov and Ungern

Grigori Semenov

The latter has his roots in Baltic Estonia. He is the descendant of German crusaders, the warlike Teutonic Knights, and later on his family builds up a tradition in military service of the Russian Tsarist Empire. His superior, General Wrangel, writes about Ungern in his memoirs: ‘War was his natural element... When he was promoted to a civilised environment, his lack of outward refinement made him suspicious.’

Semenov and Ungern are reactionary officers, devoted to Russian imperial autocracy and fanatically opposed to all kinds of democratic changes. In other words: the Tsar rules; without his supreme authority chaos is inevitable and Russia will fall apart. It is needless to say that the Russian Revolution of 1917 causes the final and fatal breaking-point in their careers.

Towards the end of 1916 Semenov and Ungern request to be posted on the Persian Front. The transfer is granted and in January 1917 they are stationed together in the Urmia region. Semenov joins the Transbaikal Cossacks, the fierce warriors of his Siberian homeland who already serve in that Russian occupied part of Persia, and he becomes the commander of a sotnia or cavalry squadron of the Third Verchne-Udinsk Regiment. That unit has its cantonment ‘in a village close to the shore of Lake Urmia’, as Semenov puts it. It is Gulpashan, the Assyrian village where about a year before his arrival Persian Muslims have slaughtered a lot of Christian villagers. Bloodshed and massacre – Semenov and Ungern are surrounded by their natural elements.

Roman von Ungern-Sternberg

Semenov and Ungern decide to counter the events with drastic counterrevolutionary action. April 1917 permission is obtained from the local Russian army staff to start recruiting new volunteers among the Assyrians in the Urmia region. They will be trained under the personal command of ‘the exceptionally brave officer Baron RF Ungern-Sternberg’, as Semenov characterizes his companion.

The Assyrian volunteers, mainly tribal warriors from the Hakkari mountains, know how to fight, but due to the revolutionary upheaval among the Russian soldiers the efforts of the Assyrian fighters fail to restore military discipline. The Russians are fed up with the war. Domoj! they shout, they want to go home.

Guerrilla and Exodus

The Russian writer Viktor Shklovsky, who serves in Persia after the February Revolution of 1917, notices that a guerrilla band under the command of the Assyrian general Agha Petros raids the country. Shklovsky writes: ‘The exiled Assyrian mountaineers starved, plundered and aroused the burning hatred of the Persians. They visited the bazaars dressed in small felt caps, multicolored vests and wide pants made from scraps of calico and tied above the ankles with ropes. The Christian religion, which bound the Assyrians together, had long since grown slack and subsisted only as another means of differentiating them from the Muslims.’

Apparently with the support of Semenov Ungern has trained a tough Assyrian militia, fit for guerrilla fighting and eager to annihilate the enemy. No mercy, raid and kill – it is the kind of warfare Semenov and Ungern will put into practice during the civil war in eastern Siberia. Is it far-fetched to presume that the uncompromising behaviour of the Assyrian warriors has inspired them to some extent?

Chal castle - Soto's stronghold

The Assyrian expeditionary force engages in heavy fighting against the Oramar Kurds. Assyrian warriors conquer and sack Oramar. Soto has fled and the Assyrians hunt him down in his last mountain stronghold at Chal. In a dashing attack they storm the castle and break through its main gate. The Kurdish defenders are slain, others are taken captive and the fortress is burnt to the ground. Soto himself has escaped once more, but the Assyrians have ravaged his territory and back in Urmia they get their reward – Russian military medals for bravery under fire. Viktor Shklovsky cynically points out the other support the Assyrian fighters have got from their Russian allies: ‘We gave them nothing but rifles and cartridges, and even the weapons supplied were mediocre French three-shot Lebel rifles.’

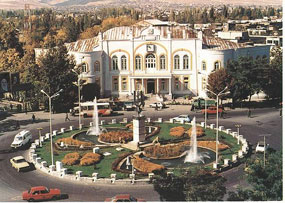

Urmia today - Central Square

The Assyrians have just one option left – a general exodus. The whole Assyrian nation, men, women and children, flee in a desperate attempt to reach the advance guard of a British expeditionary force that is approaching from the south. After the Russian retreat the British have promised to support the Assyrians, but promises is once more the only thing the Assyrians get. They are constantly under attack, there is no food, no shelter, and thousands of Assyrians perish during that awful march of a whole month through the Kurdish mountains of Persia. Those who make it are assembled by the British and taken to a refugee camp north of Baghdad. That summer of 1918 marks the end of the Assyrian nation in the Urmia region. It is also a turning point in the life of Semenov and Ungern, but for them it means the start of their most notorious exploits.

Siberian Warlords

End 1917 Semenov and Ungern prepare their next move in Manchuli, a gloomy garrison town in eastern Siberia at the Russian-Chinese border. According to them Russia will perish without the Tsar, whose autocratic regime must be restored at all costs. Semenov has been in Petrograd in the summer of 1917, a few months before the Bolshevik October Revolution. He has seen the Petrograd Soviet in action and he is absolutely convinced that the Soviet is dominated by deserters and German agents like Lenin and Trotsky. It is time to stop them.

The first weeks of 1918 Semenov and Ungern advance from their Manchurian base in northern China with a small force of Buryat cavalry and Russian officers. They engage in guerrilla fighting against the Red Guards along the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Semenov’s men are pushed back, but in the summer of 1918 anti-Soviet rebellions break out in Siberia. The Bolsheviks are obliged to loosen their grip and Semenov’s Special Manchurian Detachment dashes again into Siberian Russia. He conquers the major railroad centre Chita and makes this town the capital of his territory.

Civil war with Reds fighting against Whites tears the Russian Empire apart. The former tsarist admiral Kolchak is in full control of the White Siberian government established in Omsk, west of Lake Baikal. The Siberian Far East is set ablaze. Japan has sent a contingent of troops, while an American expeditionary force is about to disembark in Vladivostok. In Transbaikalia, east of Lake Baikal, Semenov pulls the strings with money and weapons he gets from the Japanese. He is promoted ataman, supreme leader, of the Transbaikal Cossacks and that period in Transbaikalia is called the Atamansjtsjina, which means the Ataman’s Reign of Terror. His armoured trains terrorize the area and other trains get the even worse reputation of death trains. They transport Bolshevik prisoners of war to their doom. The Red captives are executed along the way or starved to death and when such a train stops at last on a side track near a station the stench of the corpses in the closed wagons is almost unbearable.

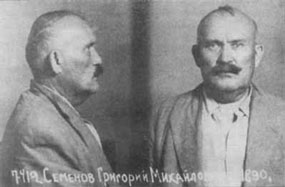

Ataman Semenov in Soviet jail

Finally he settles down in Chinese Manchuria, a puppet state of Japan after 1930, and there he keeps agitating against Soviet Russia as the leader of the White Cossacks. At the end of the Second World War the Soviets invade Manchuria. Semenov is arrested, put to trial and sentenced to death by a Soviet court. End of August 1946 he is hanged in a basement. The Bolshevik hangmen prolong his agony and shout at him Repent, reptile! And that is how die-hard Cossack warlord Grigori Semenov meets his end.

Back to 1920. Semenov still rules in Transbaikal Siberia when Ungern claims his own dominion at the Manchurian border. Russian refugees heading on trains for China are robbed and thank their good fortune if they get through alive. Ungern is equally ruthless towards his own men, a bunch of wild and often sadistic warriors. Drunkenness and attempts to desert are severely punished. Flogging to death is one of Ungern’s methods. ‘Did you know’, he once said, ‘that men can still walk when their flesh is separated from their bones?’

In the autumn of 1920, when Semenov is about to leave Transbaikalia, Ungern starts his most stunning campaign. He invades Mongolia with a cavalry division of Mongolians, Cossacks and Tibetans, altogether some five thousand troops. The Tibetans have been sent to him by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, who hopes that Ungern’s army will free Mongolia and Tibet from the Chinese. The first attack of the invaders is driven off, but in February 1921 Ungern’s men storm the Mongolian capital Urga (Ulan-Bator), they massacre the Chinese garrison and sack the city.

Ancient times of terror and bloodshed revive in Urga during Ungern’s rule. He adopts the features of a militant Buddhist, as appears from his new colourful outfit. In the eyes of his Mongolian followers he is the God of War, the incarnation of Genghis Khan, and he reveals his ultimate plan – restoring the Great Mongolian Empire through fire and sword. He will advance against Soviet Russia and, as he puts it, create a lane of gallows with the corpses of Bolsheviks and Jews.

Ungern in Mongolia

In September 1921 he stands trial in a Soviet court in Novosibirsk. When asked by the Bolshevik prosecutor, a Siberian Jew, if he often beat people to death, Ungern answers: I did, but not enough! He is put before a Red firing squad and executed. Legend has it that Baron von Ungern-Sternberg even in better times more than once declared: Ich war ungern von Sternberg. In English: I have always hated being me.

Semenov and Ungern – after the Great War Siberian warlords of the worst kind and in the spring of 1917 Russian Cossack officers training Assyrian militias in the Persian Urmia region. The Russian writer Viktor Shklovsky liked the Assyrians, he called them a fantastic people. This may be true, but they have all too often picked the wrong allies. Or maybe these dubious allies picked them. Wrong place, wrong moment and wrong alliances – it seems to be the fate of the small Assyrian nation in history.

More about the dreadful events in the Assyrian village of Gulpashan, Persian Urmia region 1915: read Suria's Page, the story of an eyewitness. With thanks to her son Ron David.

Sources: Viktor Shklovsky, Sentimental Journey (Berlin, 1923); James Palmer, The Bloody White Baron (London, 2008); Jamie Bisher, Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian (New York, 2005); Ataman Semenov, O sebe (Moscow, 2002). Text - A. Thiry

|

Homeland

Homeland  East of Eden

East of Eden  Siberian Warlords

Siberian Warlords

Homeland

Homeland  East of Eden

East of Eden  Siberian Warlords

Siberian Warlords