|

THE STORY BEHIND THE TURFAN COLLECTION IN BERLIN

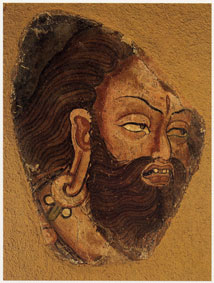

Fresco Turfan Collection Berlin

Heroes of the Taklamakan

Towards the end of the 19th century rumours circulated among archaeologists in Europe. It was said that treasures of great historical value were buried in the far west of China, in Chinese Turkestan. The central part of this enormous territory is the Taklamakan Desert. It is one of the most barren regions on earth. Taklamakan means in the local Turkic language place of no return. The Venetian merchant Marco Polo, who travelled centuries ago along the Silk Road to China, wrote about entire caravans swept away by the moving dunes of the Taklamakan. Around 1900, the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin made the dangerous journey through this immense desert and he discovered ruined cities under the sand. It was hot news in those days and thus started the race that drove other adventurers to Chinese Turkestan.

The orientalist Aurel Stein was a Hungarian Jew who went to British India and became a British citizen. Albert von Le Coq, a rich German wine merchant, sold his firm; he studied oriental languages and went to work as a volunteer in the Indian department of the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin.They were both outsiders, but it was precisely the obsession of the real amateur that fueled their dream. They became archaeological heroes, the Schliemanns of the Taklamakan.

Nestorians and Manichaeans

East is east and west is west and never they will meet. There is some truth in these words written by Rudyard Kipling, but he underestimated the historical contacts and intercultural exchanges. Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire, he invaded Central Asia and reached India. After his death the Greek heritage he had left behind in the east got mixed with Asiatic features. From this symbiosis originated the Gandhara culture, which flourished in Central Asia during the first centuries AD. Sculptures in Gandhara style often showed Buddha figures in classical Greek garment.

Later on other religious traditions took root in these regions. Nestorian missionaries of the autonomous Church of the East travelled farther east on the Silk Road and founded small Christian communities in Chinese Turkestan. Together with oriental Christianity, another religon came to the fore – the teachings of Mani. Mani was a 3th century prophet from Persia, who mixed Christian, Buddhist and Persian influences into his own religion based on the permanent conflict between light and darkness. He preached an ascetic life – no meat, no wine, no sex – for his most prominent followers, the electi. He was arrested and crucified; according to other sources his body was stuffed with straw and his head was hung on the main gate of the Persian capital. His followers fled to Central Asia and Manichaeism was widely spread in the oases of the Taklamakan till the 10th century.

Nestorian and Manichaean communities and the hard evidence of their presence in the desert of Chinese Turkestan – all got buried under the sand, together with the ruined cities, and it was forgotten for many centuries. Till Albert von Le Coq and Aurel Stein started out, in search of the lost treasures of the Taklamakan.

Foreign Devils in Turfan

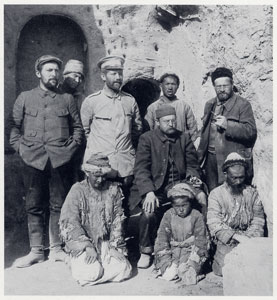

German expedition - Von Le Coq standing far right

The Turfan oasis lies in a large geological depression and it is irrigated by subterranean canals with melting water from the high mountains to the north. Yet the whole area around Turfan is terribly hot and arid and it hardly ever rains there. In this blistered landscape, as if it were on another planet closer to the sun, Von Le Coq and Bartus had to spend several months. While exploring the deserted ruins of the ancient town of Karakhoja or Khocho, they found a fresco representing Mani – the first picture of the prophet ever found – and they also discovered fragments of marvellously illustrated manuscripts, apparently belonging to a Manichaean library.

Turfan - Palm Sunday Fresco

Von Le Coq and Bartus celebrated these first discoveries with a nice cool bottle of Veuve Clicquot champagne from the box Von Le Coq’s sisters had given their brother as a present when he left for China. It was a real treat and so they could at least for a short while forget the Turfan agonies: meals of mutton-fat mixed with rice, heat and dust, and enormous cockroaches. It was enough to make a man really sick to wake in the morning with such a creature crawling all over his face, Von Le Coq wrote in Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan.

Cave temples at Bezeklik - Chinese Turkestan

It meant a lot of hard labour, but it was all executed with good old German accuracy. Von Le Coq used a sharp knife for the first incision around the frescoes and then Bartus cut them free from behind with a saw. They put the large paintings between layers of felt and cotton wool on wooden boards and so they transported whole packages in well-protected crates. In the same way they removed equally stunning Buddhist paintings, fifteen centuries old and almost purely Hellenistic in character, from the caves of the Kyzil temple to the west of Turfan. By Von Le Coq’s own account not a single fresco got damaged during the long and hazardous transport from Turfan through Russia and finally to Berlin.

One of these wall paintings showed three figures, each of them striding in a solemn lifelike manner with a tiara on the head and dressed in long red gowns. They were identified as Uyghur princes, leading figures of an indigenous Turkic people that adhered to Manichaeism and only later on converted to Islam. Till today Uyghurs have represented the largest muslim population in China’s turbulent west.

The fresco with the Uyghur princes was discovered by Von Le Coq in the monastery complex of Bezeklik. It was an excellent find as Von Le Coq asserted, he arrived just in time. He described in his Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan how the ignorant and superstitious muslim peasants mutilated the faces of the figures on the Buddhist frescoes. He also noticed to his dismay that they removed the paint and used it as dung on their fields. Von Le Coq made it clear: he was the one who had saved priceless historical heritage from complete destruction. And yet, this is just one way to look at it. Von Le Coq also mentioned that the caves of Bezeklik were filled up with sand and also that the paintings in Kyzil were covered with a thick layer of white mould. All these frescoes were in fact well hidden and protected, till two German foreigners arrived on the spot, cut them free and took them away.

The Secret Library

Aurel Stein (with dog) - Chinese Turkestan 1907

Picture this scene: Aurel Stein in an almost ecstatic mood bowing over age-old oriental manuscripts that surpassed his boldest expectations. The greatest treasure that fell into his hands consisted of seven strips of paper joined together. It was the text of the Diamond Sutra, the Buddhist teaching of perfect wisdom, and, more important, the world’s earliest printed book, dating from the year 868. When the Chinese authorities finally heard about Stein’s deal with priest Wang, it was too late. Aurel Stein transported twenty-four boxes with manuscripts and Buddhist paintings on silk to his temple of science, the British Museum in London. He also admitted that the whole operation had costed the British Treasury only 130 pounds.

Great Britain showed little gratitude however. The Diamond Sutra is nowadays still displayed in the British Museum, but the precious manuscripts Stein got hold of in Chinese Turkestan have been removed ‘for further research’ to the British Library. Exit Aurel Stein. He became a nonperson; his name is not mentioned in British academic circles.

The Turfan Collection

The Taklamakan got its revenge, so it seemed. But what about Von Le Coq after his exploits in Chinese Turkestan? He was luckier, at least for the time being. Till his death in 1930 he occupied himself with arranging and displaying his treasures from China in the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin. He could act without restrictions, since he had become the director of that museum. His life’s work was about to result in long-lasting fame, and then the irony of history got its share. During the Second World War American and British airplanes bombed Berlin. The Museum of Ethnology in the heart of the capital was hit seven times and burnt down. The largest Buddhist frescoes from Bezeklik had been cemented to the walls in iron frames. They could not be removed and went up in flames. Much to the malicious delight of the Chinese. They never stopped blaming the German adventurers who had stolen all these treasures, just to save them as they pretended, but who in fact had caused their ultimate destruction.

Bezeklik fresco with Uyghur princes - Berlin

Following the archaic technique applied in Chinese Turkestan, the interior walls of the Silk Road gallery have been covered with clay and straw and then with plaster, in which Von Le Coq’s Turfan frescoes are fixed. In the centre of the gallery an accurate reconstruction of one of the Buddhist cave temples at Kyzil has been built. It took a whole team of restorers two years to decorate its interior with the wall paintings that once belonged to the original temple in Chinese Turkestan. It is all skilful German craftsmanship and it must have cost a fortune.

Stolen by foreign devils? The Chinese may have a point there. Yet it all depends on the way you look at it. The treasure hunters Von Le Coq and Stein are gone, they are dead and buried. So are the Manichaeans and the Nestorian Christians in that remote western corner of China. Fortunately they did not completely wander in vain along the Silk Road, in search of souls and salvation. Their best achievements, unique works of art, survived the sands of the Taklamakan. No need to make the dangerous journey to that desert from where few returned. Just go to Berlin, where eastern splendour and western greed together created the Turfan Collection. A thing of beauty, a joy forever.

The Museum of Indian Art is close to the subway station Dahlem Dorf in SW Berlin.

For more details about the treasure hunters – see Peter Hopkirk, Foreign Devils

on the Silk Road (Oxford University Press, 1980).

|

Homeland

Homeland  East of Eden

East of Eden  Raiders on the Silk Road

Raiders on the Silk Road

Homeland

Homeland  East of Eden

East of Eden  Raiders on the Silk Road

Raiders on the Silk Road