|

End 1924 the League of Nations decided to send out the Mosul Commission. It had to gather material that would allow to solve the hot issue of the frontier between Turkey and the new state of Iraq under British mandate. One of its three members was a Belgian, Colonel Albert Paulis. In this article, Marc Dassier reveals details from his diary, which was written in 1925. Albert Paulis – a hero of the Great War and a most honourable man who was touched by the fate of the Assyrian Christians.

A. Paulis (sculptor Oscar Nemon)

Muslims and Minorities

According to A. Paulis, King Faisal of Iraq stated in his welcome speech to the Commission that the Mosul Vilayet had a population of 300.280. There were 173.000 Arabs, the others belonged to minorities: 59.380 Kurds, 16.000 Turkomans, 30.000 Christians, mainly Chaldeans, 6000 Jews, 14.900 Yezidis and 1000 from other religions. This means that according to King Faisal, the region was predominantly inhabited by Arabs. This is in contradiction with a document from Einar af Wirsén on the ethnic composition in the Mosul Vilayet including Kirkuk: the Commission stated that with half a million out of 800.000 people the Kurds were the majority in the Mosul-Kirkuk region.

Map of northern Iraq - the area where the Mosul Commission had to work in 1925

In any case, these statistics confirmed the existence of important minorities in the disputed area. A lot of people of all communities were interviewed by the Commission in various localities in the Mosul Vilayat. It soon became obvious that the Commission had to work in a melting pot of cultures and religions and that it would have to inform the League of Nations Council on the poor status of persecuted minorities, mostly Christians. On the other hand, Paulis explained to the representatives of the minorities that the Commission had to focus on the accuracy of the northern frontier between Iraq and Turkey, according to the Brussels Line established at the Brussels Conference of the League of Nations, rather than to promote an impossible autonomy for each minoritiy.

Tales of Horror

A. Paulis wrote in his diary that the Assyrians sided with the Russians in the First World War. After the retreat of the Russians and also after the Great War, the Assyrians sided with the British against the Turks, who organized another punitive expedition against them in 1924. The Assyrians had to run and from September 1924 onwards they were temporarily sheltered in and around Mosul. According to Albert Sassoon, director of the Israelite Alliance schools in Iraq, the Christians were persecuted by the Turks during the Great War because they had attempted to get rid of the Ottoman Empire, but the Jews were left in peace because of their neutrality.

A. Paulis met Mgr de Berré, Catholic archbishop of Baghdad and apostolic delegate to Iraq, who was in the Turkish city of Mardin in 1915 when the Christians were slaughtered there. A delegation of refugees from Jezira or Cizre in Turkey – three men and a woman – told horrible stories about what happened in 1915. Particularly touching was the fate of the woman, whose family and children were massacred under her eyes by Kurds during a pillage. Four of her nieces were sold many times, they were still in the hands of Kurdish aghas and she had no news from them. The woman, originally rich, had to become a maidservant. The Turks sold the Christian properties to local Kurds at a ridiculous price and even that little money was never received. When the fugitives arrived in Zakho from Cizre, they were protected by the local leader Mohammed Agha, who was opposed to the massacres.

Some other ecclesiastics reported that after the Great War the Christians were no longer slaughtered in Turkey, but they also mentioned that after the Greek invasion into Turkey and the war of the Turkish Republic against that invasion in 1923, the Christians were expulsed from Turkey. In fact, the kemalist government in the Turkish Republic under Atatürk was more xenophobic and anti-Christian than ever. According to Mgr Joseph Simon, patriarchal vicar of the Persian Assyro-Chaldean refugees, these pitiful people, harassed by their Kurdish neighbours, left their homeland in NW Persia at the end of the Great War. From 65.000 they fell to 30.000, due to the massacres and the hardships in exile. The British government kept them in a refugee camp close to Baghdad, but some of them left this torrid plain and returned to their Persian homeland at their own risk. Nothing was heard of them since then.

Another episode of ethnic violence was told to A. Paulis by Colonel Lawrence, commander of the Levies Regiment and by other informants. It was known as the Kirkuk Incident. In the summer of 1924 an Assyrian soldier of the city garrison was hit during a futile dispute in the bazaar of Kirkuk. Assyrians put fire to some shops and killed about twenty Muslims. The Assyrian regiment was kept in the barracks when the Muslims from the bazaar retaliated against the local Christians and killed a dozen of them. Both parties blamed each other for the bloodshed. The Christians claimed that the fighting was organized in Turkey; the Muslims said that the Assyrian soldiers acted as if they had conquered the town.

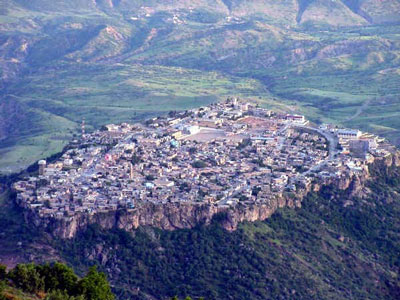

Recent picture of the town of Amadia - northern Iraq

In Dohuk, a town to the north of Mosul, the Commission noticed a lot of Assyrian refugees among an obviously pro-Turkish population. Many inhabitants spontaneously kissed the hand of Javad Pasha, the Turkish assessor to the Commission. Two Chaldean priesters from a village of 200 Christian families, surrounded by Muslim villages, told the Commission that positive contacts with the Muslims were restored after the Turks had left the country. Under Turkish rule Christians were robbed and beaten, most of their claims were ignored and a lot of local Christians disappeared. Paulis noticed that the Christian houses were clustered or built like little fortresses and he wrote : ‘We are struck by the difference between the clean and well-built Christian villages and the Turkish and Kurdish villages and towns we visited. Af Wirsén, de Teleki and me share the feeling that we are in a more civilized environment.’

Other testimonies came from delegates from Amadia, a small town in the mountainous area north-east of Dohuk. In Amadia there were 9000 Assyrians and Chaldeans and 2000 refugees of the Assyrian Tyari tribe from the Hakkari mountains in Turkey. The Amadia delegation was led by Mgr Francis, Chaldean bischop of Amadia, and other priests in this area. According to them, general massacres against the Christians had not taken place there, only isolated murders, and some Turkish officials had encouraged the Kurds to attack the local Christians. Before the Great War daily exactions were coming from the Kurdish aghas and persecutions had increased under the government of the Young Turks. Two years ago, when the Turks had invaded Rawandoz close to the border with Persia, the Kurdish agha Abdul Atif had attacked two Christian villages and slaughtered 72 villagers. Kurds and Christians could leave in peace, but the Kurdish aghas were stirring up their people against the Christians and according to the Christian delegates from Amadia, most Kurdish aghas were in league with the Turkish government.

About the Assyrians

Western clerics, who had lived with the Assyrian Christians from Hakkari in Turkey, gave Paulis a description of the former Assyrian homeland. In the past the Assyrian tribes were nearly completely independent in their mountains. They paid a tribute to their patriarch to administer the land and retribute the Turks on an annual basis, in order to be left in peace. The Assyrians had their own laws and traditions, and their customs were very primitive. Murder could be made up by payment, but the family of the victim kept the right to kill the murderer or one of his close relatives. Robbery was subject to a financial penalty. In case of adultery the deceived spouse had the right to take the law into his or her own hands. The possessions of a deceased man were divided among the sons, but the daughters were excluded, because most of the time they married into another clan and personal assets could not go to another tribe.

The temporal and religious power was executed by the Assyrian patriarch Mar Shimun, whose High Office had become hereditary within the same family. The patriarch having been slaughtered by the Kurds in 1918, the power was first executed by his brother. A few months later this successor died from illness and was replaced by his nephew, who was consecrated when he was only 11 years old. The present Assyrian patriarch, 17 years old in 1925, was studying in England. So it happened that for the time being the spiritual authority fell to the assembly of the Assyrian bishops, while Lady Surma, the young patriarch’s aunt, got hold of the political leadership.

Lady Surma - Mar Shimun's aunt

Assyrian claims

The Commission asked the Assyrians about their views on resettlement. If they were incorporated into Turkey or Iraq, would they be satisfied with local autonomy, paying a tribute through their own patriarch, as they did in the past? Some of the Assyrian petitions asked the League of Nations to create a new territory for the Assyrian nation, where they would be fully independent under British protection, without further interference from Turkey or Iraq. Lady Surma clearly stated: ‘With no solution found by the League of Nations, our people will be obliged to become expatriates.’ The Commission also met a very old Assyrian, who opened up his heart and explained what should be done: ‘In the past we were independent and we lived in peace with our neighbours. Today, we are dispersed and we have to live in exile. For many generations we have been Christians and we kept our faith despite all difficulties. We are just asking to get permission to rebuild our churches and our houses. But it should be obvious to all that we also need a territory where we can cultivate the land and feed our people.’ The Commission explained that his wish was impossible, because they would be living in their mountains surrounded by Turks, Arabs and Kurds, and no European power could defend them there against future aggressions.

Mosul Commission - Sitting: A.Paulis (second from left) & Af WirsÚn & de Teleki

Other Assyrian supplications expressed the wish to remain in Iraq if real protection was guaranteed, since Arab domination would not be able to control the Kurdish aghas. Another bishop stated: ‘With British support safety will be ensured, because the British are strong and feared. If there is only Iraqi domination, there will be anarchy, persecutions and massacres.’ The Commission promised to take into account the miserable situation of the Assyrians. According to A. Paulis, Sir Henry Dobbs, the British High Commissioner to Iraq, had a meeting with the Commission in Baghdad on 24 January 1925. He mentioned the case of the Assyrian Christians and showed a letter, written in April 1924, from the British government in London to the President of the Iraqi Council. In this letter the Iraqi government was recommended to give local autonomy to the Assyrians. It was told that King Faisal had approved of it.

Paulis in the Congo

Albert Paulis was born in 1875. He graduated from the Belgian Military School and at the start of the 20th century he was sent by King Leopold II to the Congo Free State, Leopold’s private dominion that became a Belgian colony in 1908. Paulis established Belgian posts in the region of Bahr El Ghazal in southern Sudan. The Belgians wanted to explore, to make scientific observations and to fight against slavery, but above all they wanted to control the region. By predicting a lunar eclipse that took place at the best moment, A. Paulis terrorized the local tribal leaders, the partly arabized and superstitious Azande sultans, and in this way he was the first to gain control over this hostile territory. With the support of the local tribes he resisted the British forces, who had started a siege in response to this new Belgian annexation in the name of King Leopold II.

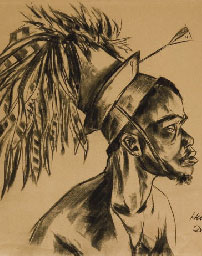

Azande tribal chief 1930

Albert Paulis was also a hero of the Great War. After having been Head of Staff Office for Louis Franck, the Belgian Minister of Colonies, he went back to the Congo, where he was active in various companies and built important railway infrastructure. He was known as Le Broussard or The Bushman and he died in 1933, exhausted by his work. In 1934, the city of Isiro (in Uele, North East Province of the Congo) was renamed Paulis. This place got its old name back under Mobutu’s regime, which destroyed all traces of former Belgian colonization.

The British Way

Albert Paulis, a rationalist, was just a well a man of intense emotions. This is made clear in his diary that covers the period when he was active in the Mosul Commission. So, back to Iraq in 1925. At Lady Surma’s house, where Assyrian families were sheltered, he noticed : ‘We observe the women and the childeren walking in the court, they look like poor refugees. This is really heart-rending.’ On another occasion in Mosul he wrote about an Assyrian delegation: ‘How pitiful it is to observe these banished people going away, bending their back under the falling snow. They do not come by car, they have no brass band and no flags, they only keep a firm trust in the future. This reminds me of similar processions in August 1914 along the roads in Belgium, my fatherland.’ Paulis refers to the first days of the Great War, when German troops invaded Belgium and huge crowds of Belgian citizens fled from the aggressors. Belgians on the run and Assyrian refugees – memories and more recent observations are melted together into an appalling scene of blood, sweat and tears.

Miss Gertrude Bell

Paulis wrote that on the occasion of a dinner he criticized Miss Bell and stated that her openly quarrelsome attitude towards the Turkish guests was intolerable. This episode may have upset her and it may have stirred up her prejudices against him. On the other hand and in spite of her distrust of the Turks, Miss Bell described Javad Pasha, the Turkish delegate in the Commission, as an old and harmless assessor. Was he really so peaceful? A. Paulis wrote in his diary that in September 1924, only a few monts before the arrival of the Commission in Iraq, General Javad Pasha led an attack of Turkish troops against the Assyrians in the area of Amadia. This 'harmless' man also organized in 1915 the strong Turkish defence of the Galipoli Peninsula against the Anglo-French military expedition in the Dardanelles.

The Mosul Commission had been received in Turkey before coming to Iraq. That was sufficient for Gertrude Bell and other British officials in Iraq to suspect its members of being pro-Turkish. The Commission nevertheless clearly marked the frontier between Turkey and Iraq in its report to the League of Nations. Iraq under British mandate got the Mosul Vilayat, Turkey kept the Hakkari mountains. What about the Assyrians? They got nothing, they only kept the memories of their lost homeland in those mountains. Gertrude Bell died a lonely death in Baghdad in 1926.

Adapted from the English text by Marc Dassier (editing & illustrations - ATH)

See also original French article by Marc Dassier: Le carnet irakien du Col. Albert Paulis

|

Homeland

Homeland  Iraq

Iraq  Albert Paulis in Iraq

Albert Paulis in Iraq

Homeland

Homeland  Iraq

Iraq  Albert Paulis in Iraq

Albert Paulis in Iraq