|

The Khabur flows through a desert plain in the northeastern corner of Syria. Both banks of the river are dotted with thirty Assyrian villages. The Assyrian Christians, who live a quiet life in those settlements, once had another homeland, the Hakkari mountains in eastern Turkey. How did they end up in the Khabur region and how does this Assyrian enclave look like these days? Trouble in paradise – impressions of a journey along the Khabur in the autumn of 2009. (Text August Thiry - Illustrations ATH, Dirk Neven, Geert Segers) Bishop Atnel frowns. ‘Are you a journalist?’ he asks. I close my notebook and Father Afrem, who has introduced me to the bishop, clears his throat. Heavy silence fills the room. Journalists are apparently considered to be dangerous people here – they spread rumours, fabricate sensation and put pictures of nude women in newspapers.

Inner court of Syrian Orthodox Saint Mary's Monastery at Tel Wardiat

I had crossed the Turkish-Syrian border at Nusaybin-Qamishli on a calm October day. A Kurdish taxi driver, who was smoking all the time, brought me to Hassake, the main city of the Khabur region in the northeastern corner of Syria. We were driving through a flat desert landscape. Summer had passed, the weather was changing. The driver pointed at the bleak clouds in the autumn sky: the first rain was coming. We reached Hassake and went on to the village of Tel Wardiat. There it was, Mort Meryem, the Syrian Orthodox Saint Mary’s Monastery.

Saint Mary’s Monastery is a most wonderful place in the middle of nowhere. It looks like an oriental marble palace with a splendid inner court and guestrooms on the upper floor. Consecrated in 2000, the monastery is the spiritual centre of the Syrian Orthodox Church in the Khabur region. Bishop Matta Roham, the founder of the monastery, was absent and I was warmly welcomed by Father Afrem, the cheerful host in the black dress of the Orthodox clergy. When he asked about my programme, I explained that I had scheduled a meeting with the Assyrian bishop Atnel in Hassake.

Oriental Christians are a small minority in the Khabur region. There are Catholic Chaldeans in the region and they have a magnificent new cathedral in Hassake, but the Syrian Orthodox Church has substantially strengthened its position among the local Christians. There is a Syrian Orthodox grammar school in Hassake where Christian boys and girls get high standard education, and nowadays the greater part of the local Christian community adheres to the Syrian Orthodox faith. So Father Afrem was slightly surprised that I was primarily interested in the Assyrian Christians, the so-called Nestorians, who follow the Church of the East. According to Father Afrem these Assyrians were simple farmers, living in their villages on the Khabur River. ‘Of course, they are good Christians too,’ he concluded. He was fully prepared to drive me to the ofice of the Assyrian bishop Atnel in Hassake.

A journalist? Not at all! I do the best I can to convince bishop Atnel of my honest intentions. I assure him that I am truly interested in the history and the culture of the Assyrian community, I drop the names of Assyrian contact persons, I mention an old acquaintance – Nicholas Al Jeloo, a young and brilliant Assyrian academic from Sidney, Australia. Bishop Atnel is astonished. Nicholas? Nicholas is doing research in the Khabur region just now! Bishop Atnel dials a number on his mobile and a few moments later I can speak with Nicholas. What a coincidence, he says. Of course he will meet me tomorrow and of course we will visit the Assyrian villages together. I give the mobile back to bishop Atnel. His face has brightened up, it is quite a relief for him. He will leave me in the hands of Nicholas, the best possible guide.

The Long Goodbye

Assyrian homeland in Hakkari mountains - ruins of Qodshanes

In the 19th century Assyrian mountaineers were living as an isolated community of Nestorian Christians in the Hakkari mountains at the eastern border of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. They were subdivided into tribes. These tribes – Tyari, Tkhuma, Diz, Baz, Jelu – had their own Nestorian qashas or priests and were ruled by their maliks or local chieftains. The supreme secular and religious authority was the Assyrian patriarch Mar Shimun, whose office had become hereditary within one family clan. Islamic intruders – Kurdish neighbours and Ottoman authorities – frequently harassed the Assyrians in their last homeland, but the fatal blow came after the outbreak of the First World War.

At a general meeting of the Assyrian maliks in 1915, Mar Shimun decided to join the western allies Great Britain and Russia. He declared war on Ottoman Turkey. The consequences were dramatic. Turkish troops, supported by Kurdish bands, invaded the Assyrian homeland. After tough resistance Mar Shimun and his people fled from Hakkari over the Turkish border to Persia. In those days that part of Persia around Lake Urmia was occupied by Russian troops. The Russians formed armed battalions out of the most warlike Assyrian refugees and used them as combat forces against plundering Kurds and rebellious Persians.

In 1917 the revolution broke out in Russia. The Russian troops withdrew from Persia and left the Assyrians to their fate. The Assyrians turned to the British, who were advancing through Mesopotamia and promised to support them in the struggle against the Turks. Early in 1918 the Assyrian patriarch Mar Shimun negotiated with the Kurdish chieftain Simko about a coalition. It was a perfidious trap. Mar Shimun was ambushed and murdered by the Kurds. Looking for revenge, the Assyrian mountaineers occupied the city of Urmia on the west bank of the lake and held out in that stronghold till the summer. Then the Turks broke through the Assyrian lines and general panic swept over Urmia. The Assyrian mountaineers – armed fighters, elderly people, women and children, the whole Assyrian nation in fact – fled from Urmia to the south, in a desperate attempt to reach the British advance guard. On their long march in the burning sun of the hot summer of 1918, thousands of Asyrians perished under Turkish, Persian and Kurdish attacks. The surviving Assyrians were finally protected by the British army and taken to a refugee camp north of Baghdad.

Syrian adventure

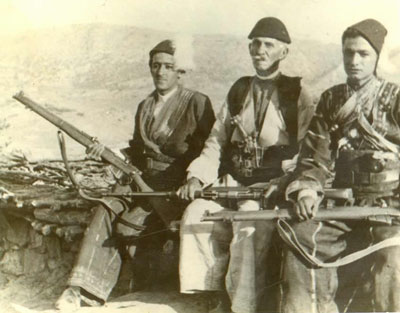

Fighters of Assyrian Tyari tribe in Iraq (picture from Tyareh Blog)

After the war the Turkish territory in the Middle East was split up by the League of Nations into spheres of influence controlled by France and Great Britain. New states were created – Syria was put under a French mandate and the British supervised the kingdom of Iraq. In the early twenties the British had to cope with revolts in the north of Iraq, where Kurdish tribes were struggling for autonomy. The British found a solution. They transferred the Assyrian mountaineers to the north and resettled them in villages in that region. The British also recruited soldiers among the Assyrian refugees and trained them for battle against the rebellious Kurds. Needless to say that these combat forces, the Assyrian Levies, were hated by Kurds and Arabs alike as Christian mercenaries under British rule. Meanwhile the new Assyrian patriarch – another Mar Shimun, educated in England – had returned to Iraq. Refusing to give up his position as the political leader of the Assyrian nation, Mar Shimun and his influential family came into conflict with the Iraqi government and with some of the Assyrian maliks. The internal conflict weakened the Assyrian minority in Iraq even more and worse was to come, as the British mandate came to an end in 1932.

The next year dramatic events took place in northern Iraq. Malik Yako, chieftain of the powerful Tyari tribe, resigned as officer of the Assyrian Levies. Together with Malik Lawko, leader of the Assyrian Tkhuma tribe, he spread the rumour that the French would give land to Assyrian settlers in Syria. In the summer of 1933 armed Assyrian tribesmen crossed the Tigris River. On the Syrian side they were disarmed by the French mandatory authorities. A few days later the Assyrian tribesmen got their rifles back from the French and while crossing the Tigris again to Iraq, they were fired on with machine guns by Iraqi troops. The Assyrian fighters retaliated – they drove the Iraqis back to their headquarters in the Chaldean Christian village of Dairabun, they attacked that military camp at night and killed 33 Iraqi soldiers.

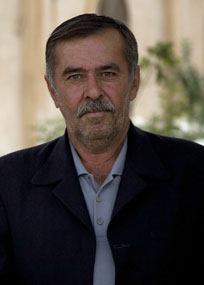

Malik Yako (photo Tyareh Blog)

Along the Khabur

Khabur guide Nicholas Al Jeloo

We follow the main road to Tel Tamir. ‘Most villages were built on flattened hills in the desert plain,’ Nicholas explains. ‘The region was almost uninhabited before the Assyrians came here. The only landmarks were these hills, they had Arabic names and the Assyrians adopted them for their villages. Tel Hafian for instance means Barefoot Hill in Arabic.'

The majority of the Assyrian villages are inhabited by descendants of the Tyari and Tkhuma tribesmen who crossed the Tigris in 1933. Tyari people occupy six to eight villages, Tkhuma people are spread over eleven settlements. The leader of the Tyari tribe, Malik Yako, died in 1974 while negotiating with the Baath regime in Baghdad. His son Zaya Malik Yako – an old politician himself with his family residence in the old centre of Tel Tamir – was a member of parliament, who represented the Assyrian minority in Damascus. Some Khabur Assyrians have claimed that Zaya Malik Yako won elections by using fraud, but these are rumours and I have promised bishop Atnel in Hassake to avoid mentioning murky affairs and dangerous political issues. So we will stay away from Tel Tamir and make our first stop at the village of Tel Hafian.

Home at Tel Hafian

Tel Hafian is one of the two Khabur villages where Assyrians from Qodshanes live. Qodshanes on a high plateau in the Hakkari mountains was the seat of patriarch Mar Shimun. His residence was close to the patriarchal Mar Shalita church. That old Qodshanes was destroyed after the narrow escape of the Assyrian mountaineers from Hakkari in 1915. The memory is kept alive by the people of Tel Hafian, who originally came from the mountain village of Terkhunis in the Qodshanes area.

Assyrian Khabur village Tel Hafian - inside the new Mar Shalita church

Tel Hafian is a tiny settlement, a five minutes’ walk leads to the Mar Shalita church at the far end of the village. The church compound is surrounded by a low wall of mud bricks and behind that wall multicoloured spots stain a sea of white – village people are at work in the vast cotton fields under a rainy sky. To the right of the entrance gate stands a rectangular construction with a flat roof and a narrow metal door. ‘This is the old Mar Shalita church of Tel Hafian,’ says Nicholas. ‘The Assyrians from Qodshanes built it about 75 years ago, as soon as they arrived here from Iraq.’ The modest construction, a bit in decay now, resembles the Nestorian stone churches built by the Assyrian tribes in the Hakkari mountains. All these age-old churches with their low entrances and fortified walls are now in ruins and many of them are probably used as stables or storage sheds by Kurdish mountaineers, who have taken the place of the Assyrians.

The new and much bigger Mar Shalita church stands close to the old one. The new church was built in 1991 and dedicated to the memory of the last Assyrian patriarch of the Mar Shimun dynasty, the one who was expelled from Iraq in 1933. He had defiled his holy office by getting married in 1975 in the USA and that same year he was murdered in California by a nephew of the elder Malik Yako. That is another story, though everything that matters in Assyrian history seems to be connected. People with such a great sense of tradition neither easily forget nor forgive.

Shamasha Kanaan in Tel Hafian

Shamasha Kanaan is born in 1952, he has got the story of the early years from his parents and other elderly people. What about the present situation in the Khabur villages? I have heard that there are problems with the water supply for their cotton fields. Shamasha Kanaan immediately clams up. ‘There is no problem at all,’ he says. ‘The French are gone, they left the country just after the Second World War. We have a good government now, thanks to President Assad and his son and successor, Bashar al-Assad. The Syrian authorities have taken care of everything, they have given us machinery for the cotton and they don’t make any distinction between a church or a mosque. We are happy here, we have everything we need.’ His final statement leaves no room for doubt or discussion. The Khabur region is far from Damascus, but the Baath Party’s secret services are omnipresent in Syria. The story about the water problem in the Assyrian enclave will have to wait.

Miracles at Tel Nasri

View on Assyrian Khabur village Tel Nasri with Mart Meryem church

Tel Nasri on the east bank of the Khabur is the last Assyrian village before one reaches the town of Tel Tamir. The 800 villagers belong to the Walto clan, a subdivision of the Upper Tyari tribe. Tel Nasri is an important place for Assyrian religious tradition in the Khabur region, its Mart Meryem or Saint Mary’s church preserves a relic with some cloth of the robe of the Holy Virgin Mary in it.

A large community hall has been erected nex to to the equally impressive, newly built Mart Meryem church. Inside the church we meet the old Assyrian priest, Qasha Awdisho. He was born in 1928 in the city of Mosul in northern Iraq and he has seen the whole history of Tel Nasri. The holy relic is preserved in a reliquary on the altar, but Qasha Awdisho cannot show us the relic box inside. He hasn’t properly fasted, he says, and so he may not go up to the altar. According to his explanation the relic box has she shape of a cylinder. It is completely wrapped up and the exterior covering is renewed once a year on the 15th of August, the Feast of Saint Mary, when Assyrian pilgrims from al over Syria gather in Tel Nasri.

Qasha Awdisho in Mart Meryem

In Tel Nasri the Holy Mary relic was placed in three consecutive Mart Meryem churches. The first one, a simple mud brick construction, was built after the arrival of the Assyrians in the Khabur region. When the larger one that replaced it burnt down, the relic was miraculously saved and put back after the rebuilding of the church. Qasha Awdisho says that around 1968 a Catholic bishop from Rome had the intention to come to Tel Nasri. He wanted to see with his own eyes what was inside the relic, but just a week before his departure a divine voice ordered him in a dream to stay away. He understood the warning and in order to make up for his disbelief, he had a church bell sent to Tel Nasri. That bell is still hanging in the clock tower of the new Mart Meryem church, which was consecrated in 2005.

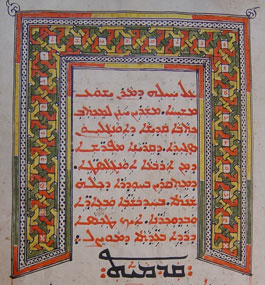

Tel Nasri - Gospel book (1758)

Nicholas takes Qasha Awdisho aside for a moment and asks something. The old priest hesitates, but finally he agrees. A bit later he comes back with another treasure, the most precious book of the collection in the Mart Meryem church. It is a lavishly illustrated gospel book from 1758. It was made in northern Iraq, in Alqosh, a place which was famous for its production of Christian manuscripts. A short annotation in the gospel book reveals the anxiety of the calligraphist who did the work: Pray for the soul of the sinful priest Yelda who wrote this. In Hakkari the Assyrians from Walto kept the gospel book in a church dedicated to John the Baptist, and later, after the exodus from their homeland, they brought it with them to Syria. Nicholas cautiously turns the pages and explains: the main text is written in Nestorian script, while the sacred and older Estrangelo script is used for the headings. ‘Wonderful!’ he says ‘The real miracle is that it is still here for us, it has been a long way from Hakkari to the Khabur.’

Happy Tel Hormiz

The rain has stopped and late afternoon is gently turning into evening, when we ride back towards Hassake and arrive at the village of tel Hormiz on the west bank of the Khabur. Tel Hormiz with more than hundred houses and a population of about 900 Assyrians is the main village of the Tkhuma tribe. It is also the home of the family clan of Malik Lawko, who together with Malik Yako and other armed Assyrians, crossed the Tigris in the tragic summer of 1933. We are welcomed in the house of the muhtar or village leader, the elderly Giorgis Yonan. Muhtar Giorgis has a vivid memory and Nicholas has a lot to translate about the settlement in Syria and about the Assyrian homeland in eastern Turkey before the Great War.

Tel Hormiz - Father Afrem in front of an old mud brick house

The Thuma tribe had a lot of maliks in Hakkari. These chieftains came out of the three most important family clans. Every two years the leaders of one family clan gathered and elected the malik from their midst and in this way each clan ruled for a couple of years. It was a traditional rotating system for the happy few, but muhtar Giorgis prefers to call it Tkhuma democracy. It is understandable: as a member of the Beth Badawi family he belongs to one of these powerful Tkhuma clans.

Muhtar Giorgis tells an amazing story about the neighbours of the Tkhuma tribe in Hakkari. These neighbours were Yezidis and the Tkhuma tribesmen were living on friendly terms with them. That is surprising. Yezidis are traditionally considered to be a separate Kurdish sect, their religion being a mixture of Persian, Christian and Islamic elements. They believe in Melik Taus, the Peacock Angel, who is according to them God’s representative on earth and not at all the fallen angel who became the Evil One or Satan in Christianity and Islam. Nevertheless oriental Christians as well as Muslims still use to call them devil worshippers. Muhtar Giorgis looks at them quite differently. Theye were in fact descendants of ancient Assyrians who were not properly christianized, he says. Yezidi people had their own place of worship in the Tkhuma area. That sanctuary with its typical tent-shaped roof was called Be Piren and it was visited by Tkhuma people when they were still in their Hakkari homeland. ‘These Yezidis were our nephews in the old land,’ muhtar Giorgis concludes.

When the Assyrians of Giorgis Yonan’s Tkhuma clan came to Syria in the mid-thirties of the preceding century, they were at first sheltered in a refugee camp close to the Turkish border. Giorgis Yonan was very young then, but he still remembers that it was a horrible place. There were almost no facilities for them, the marshy area was infested with flies and mosquitoes and the weaker ones among the refugees, mainly children and elderly people, died. A few years later the French authorities in Syria resettled them in Tel Hormiz. It was all waste land then, they had to start from scratch to build the village. The French gave them some sheep, oxen to plough the fields and simple equipment for irrigation. Muhtar Giorgis recalls the words of the French captain who was in charge of the whole operation. He came to visit the village and proclaimed at the top of his voice: Au travail! When Giorgis repeats it, it sounds like trava-trava. Move it, get to work! It is precisely what the Assyrians of Tel Hormiz did.

Tel Hormiz - Assyrian woman

Although the Tkhuma people may have kept far from politics in Syria, they got deeply involved in a religious dispute. When the Assyrian Church of the East with the seat of its patriarch Mar Shimun in the USA adopted the Gregorian calendar of western and Catholic Christianity in 1964, an Assyrian minority caused a schism. They stuck to the traditional Orthodox calendar and pledged allegiance to a rival patriarch in Baghdad. Almost the entire Tkhuma community of Tel Hormiz follows this Ancient Church of the East, as it is called, and the village is the main centre of the Assyrian Old Calendrists in the Khabur region. Muhtar Giorgis doesn’t like to speak about these matters. ‘It is all politics,’ he says. ‘We are all Assyrians, but foreign intriguers abuse religion to divide our people.’ He counters the so-called schism with an optimistic picture of Tel Hormiz. ‘We live in the best village of the whole Khabur region,’ he says. ‘We have cotton fields and orchards and plenty of vegetables. Young people get a good education and there is more than enough work for them to earn a decent living. Emigration is not a problem here, nobody wants to leave.’

Amen to that. Evening has fallen when we leave Tel Hormiz and return to Saint Mary’s Monastery, our home for the night. Nicholas laughs. ‘Very traditional, my fellow Assyrians at Tel Hormiz,’ he says. ‘There is a joke about them: they always hear the news much later, and so they think that the late Assad is still the president of Syria instead of his son.’

That sense of history

Nicholas has done a lot of research during his stay in the region. He counts at the very most 30 Assyrian villages, Arab settlers have taken over the other ones. Towards the end of the 20th century the total Assyrian population on the Khabur was estimated at fifteen thousand souls. Today there are some ten thousand left. ‘Emigration goes on and it will continue in the future,’ he says. ‘Many families in the villages get money sent to them by relatives in Europe, America, Australia and so on. That private Assyrian network provides good support for sure, but it also has a bad influence on the people here. They live on welfare in fact. They get lazy, they neglect the work on the fields, the younger people get fed up with the situation here and want to join their relatives abroad. Can you blame them for it?’

Assyrian villages on the Khabur - lack of water and plenty of cotton

Over the past decades the Syrian authorities have got more and more interested in the agricultural activities on the Khabur, especially in the profitable cultivation of cotton there. Arab colonists have been settled in villages in the region and close to the Turkish border at Ras al-Ain, where the Khabur starts its course, a great number of wells have been dug. North-west of the Assyrian villages a dam channels the water to a reservoir and there is plenty of water for the large state-owned Manajir farm in that area. Farther to the east there is another reservoir that stores dammed and diverted water for Hassake. All this has left the Assyrian settlements isolated in an arid enclave with poor water supply. In 1997 the Syrian authorities arrested three Assyrian activists, one of them a former member of parliament, who had started up a project to transport water from Hassake to the Assyrian villages. They were accused of using the funds raised from Assyrian emigrants for personal profit and of slandering the Syrian government. They were mistreated in jail and only after several months they were released.

Recent news spreads fast among the Assyrians on the Khabur. I have heard about the fate of an Assyrian correspondent. Just a few months ago he published a critical article in a local paper. He wrote that the official authorities in the Khabur region had no problem providing Arab landowners and state-owned land with abundance of water, but were unable to see to it that the Assyrian villages got the water that was left. The truth hurts, but in this case it hurt the one who had spread it. The Syrian secret service arrested the Assyrian correspondent. He was interrogated and severely beaten up. After this ordeal, which lasted for more than a week, he was released with the warning to keep his mouth shut in the future. When I arrived in the Khabur region, the man was still very upset about what had happened to him. He was hiding up in an Assyrian village, but I was told that it would be possible to visit him anyway. Better not. The poor man has got more than enough to worry about and I have promised bishop Atnel to avoid all kinds of juicy sensation.

Night has fallen. We are standing on the upper terrace of the Syrian Orthodox Saint Mary’s Monastery. The silence of the desert is all around. It is time to say goodbye. Nicholas will stay a couple of weeks longer in the Khabur region. Talking with elderly Assyrians who know about the past, taking pictures of old manuscripts, retracing the origin and the subdivision of tribal clans, preserving historical facts and figures for the next generations. Why? What is the use of it? ‘I have studied, this is what I have to do,’ he says. ‘I am an Assyrian, you know. We have that sense of history, in fact it is the only thing we have left.’ He may be right. Somewhere in the distance thirty Assyrian villages are wrapped in the desert darkness of the Khabur plain. Impossibly far away over the border in Turkey lies the lost homeland, the snow-capped mountain range of Hakkari.

Additional research, guiding & interpreting - Nicholas Al-Jeloo

|

Homeland

Homeland  Syria

Syria  Assyrians on the Khabur

Assyrians on the Khabur

Homeland

Homeland  Syria

Syria  Assyrians on the Khabur

Assyrians on the Khabur