|

The Hasnaye, former inhabitants of the village of Hassana in southeastern Turkey, have found a new home in the Flemish town of Mechelen in Belgium. They are all Assyrian Christians. Nowadays most of them follow the Chaldean Catholic Church and only a minority sticks to the Protestant faith. In the old days in Turkey, things were different.

Panoramic view with Mount Judi in SE Turkey (Photo Hollerweger 1990)

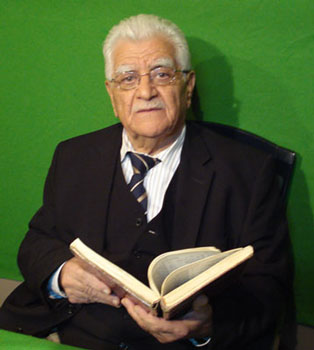

Reverend Mattai is the grandson of Qasha Mattai, the priest who guided the British explorer Gertrude Bell during her visit to the Mount Judi region in 1909 and who was slaughtered by Kurds in 1915. Reverend Mattai has been the Protestant pastor of Hassana for many years. He emigrated from his native village in 1991. He is an elderly man now, but he still perfectly remembers what is written on the memorial tablet of his church at the lower edge of Hassana. That umra or church has a small courtyard and the Aramaic inscription in the outside wall of the church indicates that the umra was built in 1833. Reverend Mattai proudly asserts that it is the oldest Protestant Beth El in the region of Mount Judi. Beth El is Aramaic for House of God. In 2004 the interior of Hassana’s Protestant church was an empty mess. Paper fragments of Aramaic prayers were thrown aside in a corner. The wooden benches were gone. There were no villagers left to sit on them and pray in the House of God.

Reverend Mattai - Protestant pastor of the Hasnaye

Reverend Mattai’s story is confirmed in the well documented historical study Ethnic Realities and the Church – Lessons from Kurdistan – A history of mission work 1668-1990, written by Robert Blincoe and published by the Presbyterian Center for Mission Studies (Pasadena, California) in 1998. Having worked in Kurdistan himself, Robert Blincoe can be considered a trustworthy source of information. Blincoe writes: ‘Which early missionary began the Protestant church in the village of Hassana in southeastern Turkey? The villagers of Hassana followed the lead of their pastor and suddenly joined themselves to the Protestant faith. The year on the church seal that I saw in Hassana is 1833. Early missionaries walked through the region as early as that date (...) This congregation [in Hassana] may be the first Protestant church in the Middle East.’ Blincoe was in Hassana and saw the church seal. He mentions that he was present on the final Easter Sunday worship service, in 1993. That was only a few months before the eviction of the last Hasnaye from their village by Turkish military.

F G Coan's autobiography

Reverend Mattai, our present-day informant, tells a similar story about the above mentioned episode and about the later events. Long ago, a Nestorian bishop – Reverend Mattai calls him Matran Yusup – lived in the mountain village of Shakh, north of Hassana. He was converted and became the first Protestant pastor of Hassana. According to Reverend Mattai, this pastor Yusup (Yosip) died in 1885 and his brother Iliya (Elea) succeeded him. Meanwhile the Canadian missionary Mc Dowell had arrived in the village. He had it arranged that two young converts from Hassana, a boy and a girl, could get their theological education in the American Urmia Mission. The girl was called Hatun and the boy’s name was Mattai. When they returned to Hassana after their studies, this Mattai, Reverend Mattai’s grandfather, became the new Protestant pastor. Hatun opened a bible-school and started teaching there as the first malpanata or female catechist in the village.

Syriac inscription on the Protestant church in Hassana

All this, Reverend Mattai’s oral testimony and Blincoe’s historical study, may be trustworthy material. There is, however, a major problem with the foundation date of the Protestant church in Hassana. Reverend Mattai and historian Blincoe stick to the year 1833, which is a highly improbable date. The American Presbyterian Mission on Persian territory was founded in Urmia in 1834. So, it is hard to believe that a year before that foundation a Protestant church was built in the remote village of Hassana, hidden in the foothills of Mount Judi in Ottoman Turkey. What if the date on the memorial tablet of the Protestant church in Hassana has been misread? This is confirmed by the British scholar Andrew Palmer, to whom I showed a picture of the inscription. Andrew Palmer has been travelling and researching in southeastern Turkey since the 1970s and he is fluent in Classical Aramaic or Syriac. He translates the greater part of the inscription written in Syriac Estrangelo script as follows: This holy house was built to the honour and worship of God, the Lord of All, in the year of Christ 1873. The year 1873 is the true foundation date of the Protestant church in Hassana. According to Palmer, the confusion is due to the fact that Syriac uses letters of the Syriac alphabet to represent numbers and the letter for the number 30 is rather similar to the one indicating the number 70.

It is interesting to notice that both the keeper of the Protestant tradition in Hassana, Reverend Mattai, and a distinguished historian like Blincoe make the same mistake. It is also amazing that a rather casual traveller got it right. His name is Tim Kelsey, a British journalist and travel writer and probably the last visitor who came to Hassana in the late summer of 1993, just before the evacuation of the village. He stayed less than an hour in Hassana. He writes on one of the last pages of his book Dervish (1996): ‘The Protestant church was built in 1873; there was a clean courtyard outside and inside wooden benches, on a sloping stone floor, and a painting of the Last Supper on the wall. The walls were clean, with a thin green wash. The benches were all at odds; it had been some years since they had last seated a congregation.’ Kelsey mentions the right date: 1873. Who informed him? We do not know. It also becomes clear that the Protestant church in Hassana is a deserted place. Reverend Mattai had left the village two years before and most members of his parish had emigrated as well. Tim Kelsey’s story is entirely accurate. But then again, who would believe a simple journalist and travel writer? We all should, so it seems after all.

Ruined houses in the old village centre of Hassana (Photo ATH - 2001)

It is time to close the circle. Further particulars can be found in the historical work The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East by David Wilmshurst (Leuven, Peeters, 2000). The author, who focuses on the old Nestorian Church of the East, mentions that a gospel manuscript was copied in 1808 in the church of Mar Mushe in Hassana by Metropolitan Joseph of Gazarta (also called Beth Zabdai, the actual Cizre in SE Turkey). This bishop depended on the patriarchate of Qodshanes, governed by the Nestorian patriarch Mar Shimun in the Hakkari mountains. Metropolitan Joseph opposed the pressure of Catholic missionaries, operating from their mission in Mosul, northern Iraq, and withdrew to the remote monastery of Mar Isaac of Nineveh near the village of Shakh on Mount Judi. He left the place that had become unsafe ‘because of war’, he settled down in Hassana in 1808 and died there in 1846. In the second half of the nineteenth century the village was for several years the residence of his successor, also named Joseph, who became a Protestant ‘with all his flock’ under the influence of the American missionaries. That successor is the one who is called Yosip by Frederick Coan and Yusup by our informant Reverend Mattai. Joseph, the successor, is mentioned in a letter of 1877 from the American Urmia Mission, which claimed as a convert the priest of the village of Hassana, ‘formerly a bishop of the old Church.’ He became the Protestant pastor of Hassana, married and was no longer recognized by the Nestorian Patriarch Mar Shimun, the leader of the Old Church. This Joseph (Yosip, Yusup) was the one who founded the first Protestant church in Hassana in 1873.

Deserted village houses at the edge of Hassana (Photo ATH - 2004)

David Wilmshurst mentions that there were 25 Protestant families and 5 Nestorian families living in the village in 1881. He also states that by 1913 Hassana appears to have been the only Assyrian village in the region without a significant Catholic [Chaldean] community. He concludes that in the 1950s the village had two churches, dedicated to Mart Shmuni and Mar Mikhail. I can add to this that nowadays these two churches, the small Mart Shmuni church in the old quarter of Hassana and the low Mar Mikhail chapel on the graveyard to the south of the village, are in ruins. Reverend Mattai’s Protestant church at the edge of the village is still there, but it is just as deserted and lost as the two other churches. It all happened yesterday, between 1873 and 1993, and it is all over now.

Text - ATH

|

Culture & Traditions

Culture & Traditions  Religion & Rituals

Religion & Rituals  Protestant Hassana

Protestant Hassana

Culture & Traditions

Culture & Traditions  Religion & Rituals

Religion & Rituals  Protestant Hassana

Protestant Hassana