|

The Colour of Our Skin

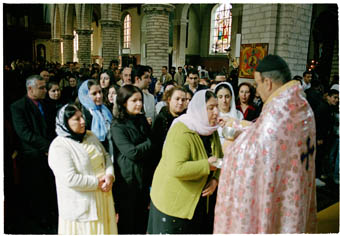

Easter at Mechelen

This is but one of the many misunderstandings Melkan explained to me when I got to know him. He guided me through his Assyrian community in Mechelen. One remark he once made summarizes all the problems of his people in the Diaspora: The colour of our skin draws more attention than the inner glow of our Christian faith. This is certainly true in a town like Mechelen, the seat of the Catholic Archbishop of Belgium, but also the place where a right-wing political party (1), which wants to kick out all non-assimilated foreigners, has become the most important faction in the city council. Assyrian refugees in Mechelen, recent newcomers from Turkey, are confronted with the frustrations and the lack of hospitality of the Flemish natives of Mechelen. Not to mention the bitter feelings these refugees have to live with in their new country, so far away from their native villages in Mesopotamia, at the border of Turkey, Syria and Iraq.

All Catholic

Mechelen has now become the hometown for 300 families of Assyrian Christians, about 1.500 people in total (2). The vast majority of them fled from the village of Hassana (Tur.- Kösreli) and gathered again in Mechelen. The Hasnaye alone in this Flemish town are made up of approximately two hundred families. Other refugees come from the same region in SE Turkey, the district of Silopi. About sixty families originate from Herbul (Tur.- Aksu) , a completely Chaldean village located east of Hassana (3). There are also about ten Christian families from the village of Bespin (Tur.- Görümlü) (4) and ten families from Geznakh (Tur.- Cevizagaci, in the district of Beytüssebap, north-east of Hassana). The other Assyrians - twenty families - emigrated from NE Syria and north Iraq. The last Hasnaye were evicted from their village by the Turkish army in the autumn of 1993. It was the biggest village inhabited by Assyrian Christians in that remote border area. The exodus from Hassana however had started years before that date.

Hassana - a name in the landscape

Only one year before Ishak had installed his family in a newly built house. But after this event, he sold his property as quickly as he could and the whole family rushed off to Istanbul. Melkan, the eldest of six children, was then only ten. On December 16, 1983 they took the first plane for Europe. When they landed in Brussels, they were stopped by the airport police since they could not show a visa for Belgium. Father Ishak pointed at his wife and children and kept making the sign of the cross: Catholic, all Catholic, he repeated. Melkan remembers the scene quite well: “It was around Christmas, few asylum seekers arrived in Belgium in those days and maybe those policemen felt pity for us. They shrugged and let us pass. As we came out of Brussels International Airport, my father raised his arms and exclaimed: ‘Thank You, Lord, You are really great and almighty!’”

Why Belgium? Two uncles of Melkan, also refugees from Hassana, had already arrived in Holland. They came to pick up Melkan’s family, so that all of them could seek asylum in the Netherlands. After Christmas however they learned that the first application for asylum, that of Melkan’s uncle Patros, was turned down by the Dutch authorities. Patros K. has kept the official document with the verdict of the Dutch Department for Immigration. Excerpts of it reveal a lot about the European attitude towards the Turkish Republic in those days:

The State Secretary of Justice, considering that law and order have been restored in SE Turkey, that the Christian minority enjoys full freedom there, that their schools, churches, seminaries and monasteries can function and that Christian literature is available there without restriction, that the Turkish authorities protect all citizens against harassments from fellow-citizens, considering also that Holland is a densely populated country, concludes that the applicant Patros K. cannot be called a refugee and therefore refuses to grant him a residence permit and orders him to return to his country of origin.

This document was the last insult. During the interrogation, preceding the verdict, the Dutch official had asked Patros whether he would have had the same difficulties in Turkey if he had been an adherent of the Islamic faith. Patros said no, whereupon the official replied that the solution was simple: Patros should have adapted himself to the general line in Turkey and become a Muslim. Melkan still knows what happened next: “Uncle Patros has always been a hot-tempered Assyrian. When he heard such an insult from an official person, he shouted at the top of his voice that he didn’t want to stay any longer in a pagan swamp like Holland. And so we all returned to Belgium.”

Predominant Catholic Belgium appeared to be a more hospitable country for oriental Christians than strictly regulated Calvinist Holland. Melkan settled down with his family in Mechelen. He finished secondary school, studied economics in Brussels and graduated cum laude. In 1989 there were already sixty families from Hassana living in Mechelen and soon more and more Hasnaye would join them. The stories of the new refugees from Hassana needed to be checked in Brussels at the Department for Foreigners and for this, the Belgian officials looked for interpreters. Melkan was the only person available who could translate the native idiom of his fellow Assyrians, the Neo-Aramaic Sureth of the region, into Flemish Dutch or French. It was an absorbing extra task. Fortunately almost all Hasnaye were granted permanent asylum in Belgium. At first they were accommodated according to the rules of the Belgian social security system for refugees; later on, when they received full recognition, they could choose where they wanted to locate. And so it happened that the majority of them reunited in a new Hassana, in Mechelen on the Tigris.

A Touch of Hassana In Mechelen the Hasnaye didn’t isolate themselves in an Assyrian ghetto. At first they had to be satisfied with small apartments in the medieval inner city. During the late nineties the Assyrians spread out to the outskirts of the town and began to buy their own houses there. The place could be old and crumbling, but no matter as long as there was a garden. Such a private green spot, small though it might be, brought back a touch of Hassana, where the villagers once cultivated their own land and gardens in the shadow of Mount Judi.

Finding employment remains a problem for the elder generation. There was scarcely any decent schooling in Hassana. A Turkish schoolmaster, who never stayed long in that remote place, was responsible for all five levels of the Hassana primary school, with children from seven to twelve years old. Turkish was the official language and the children were strictly forbidden to speak their native Sureth. Real education was never a priority: children didn’t have to attend the lessons if they bribed the teacher with a chicken or some other gift. In this way it isn’t surprising that illiteracy is still running high among the Hasnaye, especially among married women, but also among middle-aged men.

Mechelen is famous for its market of produce grown in greenhouses. Even now young, unskilled Assyrians try to earn a living in these greenhouses for the mass cultivation of vegetables. While many Assyrian fathers stay unemployed and are on welfare, a lot of their sons, though barely finished secondary school, must work, but can only find such ill-paid jobs. Assyrian girls in Mechelen still tend to marry young, with a member of their own community. Mixed marriages are an exception, perhaps because Belgians don’t bother too much about religion and divorce is on the increase, even in Catholic Flanders. Assyrian women sometimes work outdoors, though mainly as cleaners or as semi-skilled employees in restaurants, hospitals and homes for the elderly.

As for the youngest generation, Assyrian girls especially are well motivated and do well in their studies at local colleges. These young students have nothing to lose but illiteracy and there is a whole new world for them to conquer. It remains an open question though how the Assyrian community in Mechelen, which due to the influence of its old clan leaders is still clinging to traditional patriarchal structures, will react to this silent wave of emancipation, i.e. the all too modern behaviour of the younger daughters, or sons.

Great Expectations The Hasnaye clearly wish to adapt to the European way of life in Mechelen - more than 90 percent of them have requested and obtained Belgian citizenship - but they also want to preserve the core of their own culture. Religion plays an extremely important role in the life of the community and in their self-identity. Like other Assyrians, those from Hassana consider themselves the heirs of the earliest Christians, guided by the Nestorian Church of the East or by the later established Chaldean Church of Babylon. The Christians of Hassana are proud to belong to an ancient people, whose Aramaic idiom reflects the language of Christ. They feel that they are bringing the light of the Gospel once more from the ancient East to the secular West.

Qasha Toma (Mechelen 2004)

Our beloved Sureth, our Assyrian language, may it never be lost. How often have I heard this solemn pledge in Assyrian homes in Mechelen. It is a difficult task. Few Hasnaye can read and write Sureth; the language was passed on orally from generation to generation. This may have worked in SE Turkey, where the Hasnaye lived isolated as Christians. In Mechelen however many Assyrian youngsters turn their backs on their parents’ Aramaic, which sounds so unfamiliar to them. The testimony of one Assyrian girl, now married, gives hope for the future. Gazale says: “Sometimes I ask myself if learning Sureth is worth all the effort. But then I think of my grandmother: she knows only that language and if I forget our Sureth, I cannot speak with her anymore. My future lies here, not in Turkey, but I will never renounce the village of my grandmother. I want to tell my children about Hassana in her language, in the language she always used to say her prayers. My children have the right to know where their ancestors have come from.”

Solidarity, deeply rooted in the traditions of this Assyrian minority, is another key word. The last Hasnaye were evicted from their village in 1993. These villagers were the poorest ones and they arrived in Belgium without any knowledge of the new world in which they would have to live. At first these refugees stuck together and were very slow in learning the local language, Flemish Dutch. But they got financial help and assistance in the management of their affairs from the other Hasnaye, and so they were gradually re-integrated into the Assyrian community in Mechelen. Similar forms of solidarity come to the fore at weddings and funerals. Every Assyrian, living in Mechelen or abroad, is invited to such events by means of a simple phone call. And they all come to take part in the joy for the married couple or to pay their last respects to the deceased. It is a strange spectacle for the Flemish citizens of Mechelen when they see all those unfamiliar oriental faces at the entrance of a church or a wedding hall in their multicultural European town.

In addition to the Assyrians, there is also a larger minority in Mechelen: Moroccan Muslims, who came as guest workers. They have been living in Mechelen since the late 1960s and it is well-known that some Moroccan boys - a small group, as always - of the third generation, roam the streets and increase the general atmosphere of insecurity. So, there is a problem, but it is doubtful that the Hasnaye in Mechelen will contribute to a solution to the problem. They keep lodging complaints that the Moroccans enjoy advantages they do not: the Moroccans have an alderman in the city council, they get subsidized and have their own youth centre and other cultural organisations specifically for Muslims, while they, Christian Assyrians, have none of these.

Islamic infiltration is the major problem Europe refuses to face - this is the strong conviction of almost all Hasnaye in Mechelen. Binyamin, the head of a respected Assyrian family in Mechelen, speaks his mind: “We feel at home here, but I fear that the Christian faith will sooner or later disappear in this country. More and more Muslims are allowed to come and one day, when they are strong enough, they will seize it all and make it theirs. We had an old saying in Hassana: Never put a red apple into your pocket! Such an apple looked nice, but it rots very quickly. That is exactly what happens here: Muslims are like red apples in the pocket of Europe. Centuries ago Muslims, Kurds and others, came to our homeland and we all know what happened later on: they took it all and made us leave. Never trust a Muslim, he says ‘Salaam’ and shakes hands, and then he stabs you in the back.”

The Hasnaye came to Mechelen with great expectations that they would escape the yoke of Islam and would be welcomed by fellow-Christians. Disappointment followed soon. The asylum procedure sometimes took several years and even after final recognition the difficulties went on: unemployment, boredom, grey months without sun, and always stress and heavy traffic. Mechelen may be a safe haven compared to SE Turkey, but still too many Hasnaye, especially the middle-aged ones, look depressed and have to cope with psychosomatic complaints. It is the syndrome of the exile who realizes that the old home he is longing for is lost for a long time, maybe forever.

NOTES

1. The so-called Vlaams Blok (Flemish Block). In Mechelen this racist party got 26 percent of the votes at the latest local elections in 2000. In Antwerp, the capital of the province and Belgium’s biggest port, they are even heading for an absolute majority.

2. Based on local statistics from 2000.

3. Herbul had an old coalmine, but its primitive exploitation mainly ruined the landscape. Refugees from Herbul in Mechelen stick to what they call their Chaldean identity. A middle-aged man from Herbul explained to me that for the Ashuraye the Holy Virgin was the Mother of Christ, while they, the Chaldeans, prayed to the Mother of God. This spokesman, the head of a family, was a perfectly common person, and yet he still knew how to draw the ancient dividing line between ‘Nestorian’ Christotokos and ‘Orthodox’ Theotokos. As if the schism had taken place just a few years ago. Nil novi sub sole.

4. In Bespin the Assyrian Christians were outnumbered by Kurds and spoke Kurdish.

|

Mechelen on Tigris

Mechelen on Tigris  New Hassana

New Hassana

Mechelen on Tigris

Mechelen on Tigris  New Hassana

New Hassana