|

Meet the Adamov-Ivanov families in the Assyrian district of Tbilisi. Discover the work of a Georgian artist who painted with flowers. Visit an old Assyrian village in the middle of nowhere and enjoy the hospitality of its inhabitants. In other words - Kukia and Staraja Kanda, Niko Pirosmani and Roland Kandeli, David's and Ilona's story, and the Chicago blues of a kind-hearted Assyrian couple. That is all we need to mix the small Assyrian community in Georgia into a strong Caucasian cocktail. August Thiry

Home in Kukia

Pirosmani - Herder on red

David Adamov was waiting at the bus station in Tbilisi. ‘Most welcome,’ he said. ‘We will show you around and you can stay as long as you want.’ Assyrian hospitality – a characteristic preserved by Assyrians in their worldwide Diaspora. Like most of their Assyrian fellow citizens in Tbilisi, the Adamov family lived on the higher slopes across the Mtkvari river, to the north of the city centre. That Assyrian district in the green hills is called Kukia and in 2002 it was a community of more than hundred families, all together about five hundred Assyrians. It almost looked like a village, with its narrow streets going up and down, its high fences and metal gates screening the inner courtyards of the houses from the world outside. Once inside, guests were kings, well protected and only the best was good enough for them.

David introduced me to his sister Ilona, who was working for the Catholic relief organization Caritas, and to his uncle Yosip Ivanov. In that period Yosip was the chairman of the ANCG, the Assyrian National Congress of Georgia, which gives financial aid as well as social and educational support to local Assyrians. He was a modest, almost shy host; a middle-aged intellectual, small and thin, wearing spectacles with thick glasses and smiling most of the time. His wife, Marina, was much younger and an excellent cook.

Yosip’s house was spacious and half empty. I got a whole upper floor at my disposal. That part of the place had once been the apartment of Yosip’s son. He had studied medicine. After his marriage he had left Kukia for the USA and settled down in Chicago, where a large community of Assyrian emigrants lives. ‘Emigration has always been part of our history,’ said Yosip. The following month he would travel to the USA, together with his wife, to visit his son in the Windy City.

Man of Flowers

David was my guide. We stood in front of a closed and partly ruined house in the old centre of Tbilisi. It was in Pirosmani Street, named after the Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani, who used to dwell in that neighbourhood. A fine collection of his paintings was exhibited in the house, the Niko Pirosmani State Museum. I was very close, but close was as far as I was allowed to go. The earthquake that hit Tbilisi on April 25, 2002, had damaged the museum house and it would be restored as soon as the necessary funds were available and would reach the right persons. In Georgia that could – and still can – take years or be postponed to eternity. ‘Sorry, there is nobody around to persuade with a few dollars to let us in,’ said David. ‘It must be too dangerous inside. Let’s go to a restaurant. Good food and strong Kakhetian wine will soften your grief.’

Pirosmani - Cold Beer

He originated from a small village in eastern Georgia, the Kakhetia region, where the best Georgian wine is produced. Pirosmani went to Tbilisi and started up a small shop for dairy products. But he was too much of a Bohemian to keep that business going. His true passion was painting and he became a self-educated artist. In Tbilisi he frequented the dukhans, the typical wine taverns for the common people, and there he painted new signboards for the taverns and portrayed their owners and the dining and wining folk. Free food and drinks was all he got for his work. He also painted Caucasian landscapes, village life and exotic animals on oilcloth. His reputation as an artist grew, but only for a while. His excessive drinking and exuberant lifestyle largely contributed to the unhappy end: he wasted away and when he died in 1918, a part of his work was already forgotten, lost or destroyed.

Pirosmani - French actress Margarita

I had hoped that David would lead me to that very street in old Tbilisi where Pirosmani once created his truly romantic masterpiece. It was asking for the impossible. David knew about the story, but it was just a story, he explained. Nobody in Tbilisi could tell where exactly that legendary Pirosmani spectacle might have taken place.

We were sitting in a traditional restaurant in the old centre of the town close to the Georgian-Orthodox Sioni cathedral. We were eating khinkali, paste balls that looked like big mushrooms. They were filled with minced meat and spicy sauce and boiled in salted water. You had to take them with your fingers and slurp the meat and the sauce out of them. It was food for ancient Caucasian heroes or people with strong stomachs. My companion David, more than two hundred pounds Assyrian in body and spirit, ate a dozen of these khinkali. ‘We must order another bottle of wine,’ he said, ‘You must get rid of your Pirosmani blues in the Georgian way.’ If Pirosmani had still been alive and had passed there, he would have joined us; or maybe not. It was an exquisite restaurant, not one of those noisy dukhans he used to visit in Tbilisi.

Ilona’s Story

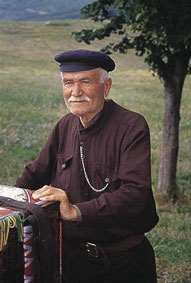

Old Georgian - Mtskheta district

Ilona told me about her roots. Her family came from the Hakkari mountains in eastern Turkey. In 1915 the Assyrians of Hakkari were attacked by Turkish and Kurdish forces and they all fled to the Urmia district in Persia. Urmia town and the region at the lake with the same name are situated in present-day Iran, close to the border with Turkey. For many centuries Urmia had been Assyrian homeland, but at the end of the First World War, in the summer of 1918, the whole Assyrian people in that area left in a hurry. They had no choice. Turkish troops and Persian and Kurdish irregulars were on the move against them; the Assyrian exodus was the only way to escape death and massacre.

Ilona’s grandparents were born in Georgia, which was soon to be integrated into the USSR as a Soviet Republic. Later on new misfortune would fall upon them. It had a name – Stalin’s terror. Ilona’s grandmother was one of those thousands and thousands of anonymous Soviet citizens who were arrested overnight and deported to Siberia. Ilona’s mother was born there, in Omsk, and she was four years old when her family was allowed to return to Tbilisi.

‘I only know Soviet Georgia from my early youth in Kukia,’ said Ilona. ‘Nowadays we have democracy and free market in our independent Georgia; and civil war on the northwest coast in Abchasia and refugees and emigration. Also in Kukia many Assyrian families are considering to leave the country.’ I asked about the situation in the Assyrian village we were going to visit in the Mtskheta district, less than an hour’s drive away. In a way it was better there, said Ilona. Those Assyrians lived from the land, they were attached to their native soil.

Assyrian Village

We reached the village of Dzveli Kanda, Staraja Kanda in Russian. Kanda is the Persian word for town – a distant echo of the Urmia-Persian roots of its inhabitants. Dzveli Kanda or Old Town is the oldest and largest Assyrian settlement in Georgia.

Assyrian village Dzveli Kanda

We walked through the main street of the village. It was a straight dirt road, intersected with smaller side-roads leading to the fields. The farmhouses in wood and stone had low zinc roofs and crumbling wooden fences. Entire families, parents and children, came outside to shake hands when we passed by. The village mayor showed up in muddy pants and boots, straight from the land. We should have announced our visit, he complained to Ilona, as visitors were guests and deserved a proper welcome. No harm done, however. The mayor guided us around. There was a primary and a secondary school in the village. That was his true pride. Education was important, he repeated several times.

The mayor also told us about the history of Dzveli Kanda. The main street was still known to the villagers by its old name – German Street. The place had once been a German settlement. These German colonists had been sent there since the time of the Russian tsarina, Catharina the Great, particularly after the Russian annexation of the kingdom of Georgia towards the end of the 18th century. Later on the Assyrians started to come. The first wave arrived in the second half of the 19th century. They were guest workers from the Urmia region, who were engaged in the construction of new houses in Tbilisi. Dzveli Kanda really became an Assyrian village during the First World War, when Assyrian refugees from the Persian Urmia-Salmas district fled to the Caucasus and settled down in Kanda.

The Germans, a minority though, stayed in the village till 1941. When Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union, they were all rounded up and deported. They never came back. Only one German woman escaped certain death. She was married to a Georgian and she was allowed to stay behind. Her son was an artist and he was still living there, said the mayor.

Another Weird Artist

Pirosmani - Wining and dining

At first sight Roland Kandeli was a fierce-looking man with a small beard and a whole bunch of grey hair on his head. He squeezed my hand in his firm grip, but it was all harmless ritual. He was a friendly chap and we were most welcome. In the house it was even a bigger mess than outside, he admitted. He had an apartment in Tbilisi and the cottage in Kanda was his workshop.

We were sitting in the courtyard, where it was nice and cool in the shade under the trees. To my surprise Kandeli was still fluent in German, but most of what he said was soon lost in heavy drinking. He made his own white wine, he said, and he told us the true story of his three wives. Three wives? He liked to change now and then, he said. But there were always problems with the cock he kept there, behind the cottage. When one of his wives came to see him, that cock always attacked her. So, he had to intervene: away with you, in the cage! The cock, he meant for sure. No, no, Kandeli replied, the woman of course! He roared with laughter. A five-litre bottle stood on the wooden table. Kandeli refilled our glasses to the brim, much to his own amusement and that of the mayor, and he wouldn’t let us go before the bottle was empty.

Staraja Kanda - Soccer team

Yosip’s Gift

The most beautiful site in Kukia is the Assyrian graveyard. It is situated on the crest of a hill. Iron fences surround the graves, packed together on that narrow burial ground. The view from there is magnificent – the silvery curves of the river deep below, the golden haze over the whole town, Tbilisi in the glow of the sunset. The dead may rest in peace; the living have to cope with everyday life in Georgia.

Assyrian graveyard - Kukia - Tbilisi

We were standing under the greenhouse glass, in the rear of his place in Kukia. It was a truly sad sight: there were just a few lemons left; oranges, cucumbers and tomatoes – all gone. Rusty gas pipes, once used for the heating of the greenhouse, were hanging there in cold uselessness. Yosip explained what had happened. In Soviet times Russia provided Georgia with free gas in exchange for Caucasian vegetables and fruit. After the independence of Georgia however, post-Soviet Russia got its fruit and vegetables elsewhere and demanded payment for the gas supply. Georgia couldn’t afford that and had to survive without the Russian gas.

Yosip took me to a storage space behind the kitchen and pointed at a heap of metal plates. It was an old stove. In winter its parts were put together. ‘We install it in the dining-room,’ he said. ‘We heat it with the wood we can get, we put our overcoats on and then we go to bed; or we put kettles with water on it and so we get hot water to wash ourselves. We have an electric boiler though, but when it is too cold, we do not get sufficient electric power to make it work. It is like old times in Siberia.’

David had told him about our bad luck in Pirosmani Street, where the museum house was closed. I went upstairs with Yosip, to his office. A whole room stuffed with books and documents and files. He went to one of the shelves and gave me a large and heavy book from the Soviet period. Niko Pirosmani - Aurora Art publishers - Leningrad 1983. It was a biography of the painter and a complete survey of his work with illustrations on glossy paper. ‘This is for you,’ he said, ‘a farewell gift.’

I was too overwhelmed to thank him properly, and carrying the book with both hands, I went down with him to the dining-room. We had our last meal together and his wife Marina had really done the best she could. It was delicious.

The next morning David and Ilona came to say goodbye – they had to go to work. When I left a bit later, Yosip and Marina were standing in the open doorway to the courtyard. It was as if they were both framed there like in a painting: a middle-aged man and his younger woman – a Pirosmani view with an Assyrian couple. They would soon go to Chicago to visit his son and try to make the best of it in a small apartment. He might be happy over there, without such romantic foolishness as spreading a flower carpet for his beloved one in the large streets of the Windy City.

Assyrian & Georgian flag united

|

Diaspora

Diaspora  Assyrians in Georgia

Assyrians in Georgia

Diaspora

Diaspora  Assyrians in Georgia

Assyrians in Georgia